SARS Virus: What Is the SARS Virus?

The SARS Virus, a highly contagious respiratory illness, caused a significant global outbreak in the early 2000s. Understanding this phenomenon is essential for appreciating the advancements in pandemic preparedness. The outbreak underscored the necessity for global cooperation and swift action against emerging health threats. It introduced the world to the challenges of combating highly infectious diseases in our interconnected world.

This section will provide an overview of the SARS Virus. It sets the stage for a detailed exploration of its characteristics, impact, and the global response it triggered. The SARS virus, or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, is a viral respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus. It’s vital to understand the SARS virus to grasp its global health impact. This virus was identified as a new, highly contagious pathogen leading to severe respiratory illness.

Definition and Classification

The SARS virus falls within the Coronaviridae family, which includes viruses affecting both animals and humans. Coronaviruses are named for their crown-like appearance under an electron microscope, thanks to their spike proteins. The SARS-CoV is classified as a betacoronavirus, a genus that includes several viruses infecting humans and causing significant disease.

The classification of the SARS virus is rooted in its genetic makeup and its ability to infect cells and cause disease. It’s an enveloped, positive-sense RNA virus, typical of coronaviruses. Its genetic material is a single-stranded RNA molecule, encoding proteins essential for its replication and survival.

Origin and Discovery

The SARS virus was first identified in Guangdong Province, China, in November 2002. The first cases were reported in Foshan, and the virus rapidly spread to other parts of the province and beyond. The discovery of the SARS virus was a collaborative effort by scientists and healthcare professionals worldwide.

The World Health Organization (WHO) was key in coordinating the global response to the SARS outbreak. They played a vital role in identifying the causative agent. Several research groups isolated and characterized the virus through molecular biology and virological techniques, shedding light on its properties and behavior.

The 2002-2004 Global Outbreak

The 2002-2004 SARS outbreak marked a significant moment in modern epidemiology. It underscored the urgency of a swift global response to emerging infectious diseases. The outbreak began in Guangdong Province, China, and soon spread to many countries worldwide.

Initial Cases in Guangdong Province

The first SARS cases were reported in Guangdong Province in November 2002. Initially, the illness presented as atypical pneumonia. Healthcare workers soon fell ill, revealing the virus’s contagious nature. The early response was hindered by limited information and coordination, allowing the virus to spread beyond the province.

International Spread Timeline

The SARS Virus rapidly spread beyond China’s borders. By February 2003, cases were reported in Hong Kong, and soon in Vietnam, Thailand, and Singapore. The virus’s spread was facilitated by international air travel, demonstrating the world’s interconnectedness and the rapid disease spread it enables. Key milestones in the international spread include:

- February 2003: First cases reported outside China, in Hong Kong and Vietnam.

- March 2003: Cases identified in multiple countries across Asia and North America.

- April 2003: WHO issues a global alert, intensifying international cooperation to combat the outbreak.

Containment Strategies

Efforts to contain the SARS outbreak were multifaceted. They included isolating infected individuals, quarantining those exposed, and improving infection control in healthcare settings. Travel advisories were issued, and airport screenings were implemented to slow the virus’s spread. These actions, along with enhanced surveillance and reporting, were vital in controlling the outbreak.

Genetic Structure of the SARS Virus

The genetic makeup of the SARS virus is key to grasping its disease-causing mechanisms and finding treatment options. It falls under the Coronaviridae family and has a single-stranded RNA genome.

Genomic Composition

The SARS virus genome is large, about 32 kilobases, and codes for various proteins. These include non-structural and structural proteins. The genome is divided into several open reading frames (ORFs). These ORFs translate into proteins vital for viral replication and assembly.

The virus’s genome is complex, with a unique replication process. It involves the transcription of subgenomic RNAs. This process produces the structural and accessory proteins needed for the virus.

Key Structural Proteins

The SARS virus has several essential structural proteins. These include the spike (S) protein, envelope (E) protein, membrane (M) protein, and nucleocapsid (N) protein. Each plays a vital role in viral entry, assembly, and release.

The spike protein is critical for attaching to host cells. It enables entry by binding to the host cell receptor ACE2.

SARS Virus Transmission Mechanisms

Understanding how the SARS virus spreads is key to effective public health strategies. The virus can move through various channels, each playing a role in its spread.

Respiratory Droplet Transmission

Respiratory droplets are a main way the SARS virus is transmitted. When someone with the virus coughs or sneezes, they release droplets. These droplets can then be breathed in by others nearby.

Fecal-Oral Route

The fecal-oral route is another critical way the virus spreads. The virus can be found in the feces of infected people. If hygiene is not followed, the virus can be swallowed, causing infection.

Fomite Transmission

Fomite transmission happens when the virus is picked up from contaminated surfaces. It then moves to an individual’s hands and face, often the mouth, nose, or eyes. Keeping surfaces clean is essential to stop this transmission.

Knowing how the virus spreads helps in setting up effective control measures. This includes better hygiene, wearing protective gear, and isolating those who are sick.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Understanding the clinical presentation of SARS is key for early diagnosis and effective management. The SARS Virus infection shows a range of symptoms, varying in severity.

Early-Stage Symptoms

Early symptoms of SARS include fever, headache, and body aches, often with diarrhea. These symptoms are nonspecific, making early diagnosis tough.

As the disease advances, respiratory symptoms become more evident, including cough and shortness of breath.

Disease Progression Phases

The progression of SARS can be broken down into distinct phases. Initially, patients may have mild symptoms that quickly worsen to severe respiratory distress.

The disease progression involves an initial viral replication phase, followed by an immune response phase. This can sometimes lead to more severe outcomes.

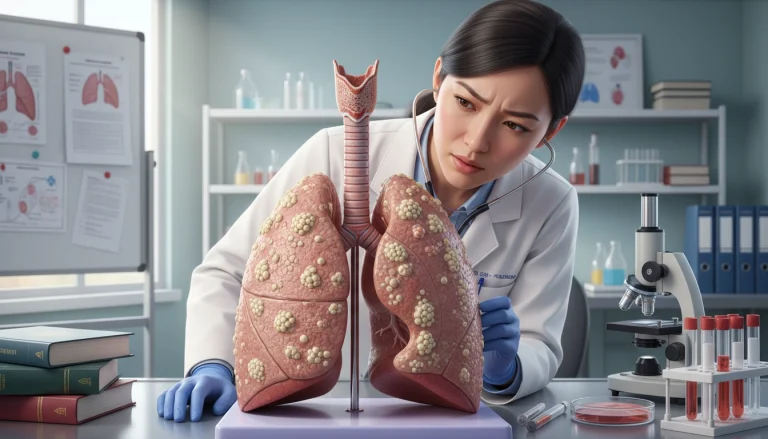

Severe Complications and Outcomes

Severe cases of SARS can lead to complications like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), requiring mechanical ventilation.

Mortality rates for SARS are around 10%. Older adults and those with underlying health conditions are at higher risk.

Pathophysiology of SARS Infections

The SARS virus starts infection by entering host cells through specific mechanisms. This triggers a series of immune responses. The virus’s ability to invade cells and the host’s reaction to it are key parts of this process.

Cellular Entry Mechanisms

The SARS virus binds to the ACE2 receptor on host cells. This is made possible by the viral spike protein, which changes shape to fuse with the host cell membrane. After entering, the virus releases its RNA genome, starting replication.

Immune System Response

The immune response to SARS includes both innate and adaptive immunity. The innate immune system tries to limit viral replication with interferons and cytokines. The adaptive immune system then takes over, with T cells and B cells controlling the infection and providing long-term immunity.

Diagnostic Approaches

Diagnosing the SARS Virus requires a multi-faceted approach. Accurate diagnosis is essential for patient care and public health. Various methods have been developed to detect SARS-CoV infection.

PCR Testing Methods

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) testing is a molecular technique for detecting SARS Virus genetic material. It’s highly sensitive and specific, enabling early virus detection. Real-time PCR is key for diagnosing SARS-CoV in the acute phase.

Serological Testing

Serological tests identify antibodies against the SARS Virus in blood. They’re vital for determining past infection and immunity. ELISA and IFA are common tests for SARS diagnosis.

Imaging Studies

Imaging, like chest radiography and CT scans, is critical for assessing SARS infection severity. They help spot lung issues and track disease progression. CT scans are more adept at catching early lung changes than chest X-rays.

Combining these diagnostic methods improves SARS diagnosis accuracy. It supports effective clinical management.

Treatment Protocols for SARS

Effective SARS treatment involves a detailed plan that includes respiratory care, antiviral drugs, and immune system modulation. The treatment’s complexity stems from its multi-faceted approach. It targets both the viral infection and the body’s immune response.

Respiratory Support Measures

Respiratory support is key for SARS patients, as the disease can cause severe breathing issues. Treatment includes supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation for severe cases, and non-invasive ventilation. These methods aim to minimize the need for invasive procedures like intubation.

Antiviral Medication Trials

Researchers have explored antiviral medications for SARS treatment. Trials have looked into the effectiveness of drugs like ribavirin and lopinavir. Yet, their ability to combat SARS-CoV remains under investigation. The goal is to find antivirals that can effectively target the virus.

Immunomodulatory Therapies

Immunomodulatory therapies aim to manage the immune system’s reaction to SARS. They aim to reduce inflammation and tissue damage. Corticosteroids have been used to dampen the immune response. Their use is debated due to side effects and the risk of delaying viral clearance.

Prevention and Infection Control

Combining personal protective equipment guidelines, hospital isolation procedures, and community mitigation strategies is key to controlling SARS Virus infection. These steps are vital in stopping the virus’s spread.

Personal Protective Equipment Guidelines

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is essential for protecting healthcare workers and others from SARS Virus infection. It includes masks, gloves, gowns, and eye protection to block exposure to contaminated bodily fluids or respiratory droplets.

Following proper PPE use, like donning and doffing procedures, is critical. Training programs are vital to ensure healthcare workers follow these guidelines correctly.

Hospital Isolation Procedures

Hospital isolation procedures are vital in controlling SARS Virus spread in healthcare settings. Patients with SARS should be isolated in single rooms with negative pressure ventilation to prevent airborne transmission.

Strict infection control practices, including hand hygiene and PPE use, are necessary among healthcare workers interacting with isolated patients.

Community Mitigation Strategies

Community mitigation strategies are key to reducing SARS Virus spread beyond healthcare settings. Public health campaigns can teach the community about hygiene practices, like frequent handwashing and proper disposal of respiratory secretions.

Measures like social distancing and avoiding large gatherings also help in controlling outbreaks.

Epidemiological Patterns of SARS

Understanding the epidemiological patterns of SARS is vital for public health. These patterns reveal how the virus spread and who was most affected. This knowledge is key to developing strategies for future outbreaks.

Global Distribution Statistics

The SARS outbreak in 2002-2004 reached over 30 countries. China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan saw the most cases. International travel and connectivity were key factors in its global spread.

- China reported the highest number of cases.

- Hong Kong was significantly affected due to its proximity to mainland China.

- International travel played a key role in the global spread.

Demographics of Affected Populations

The demographics of those affected by SARS showed a clear pattern. Adults, and healthcare workers in particular, were disproportionately hit. The virus also showed a slight preference for females.

- Adults aged 25-64 were most commonly infected.

- Healthcare workers were at high risk due to their exposure.

- Females were slightly more likely to be infected than males.

Animal Reservoirs and Intermediate Hosts

Research into the SARS virus origins has pinpointed key animal reservoirs and hosts. These played a significant role in its transmission to humans. Grasping these zoonotic dynamics is essential for understanding the virus’s emergence and spread.

Bat Origins of SARS-CoV

Bats are identified as the natural reservoir of SARS-CoV. Studies reveal that bats carry a variety of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV relatives. The genetic similarity between bat coronaviruses and SARS-CoV indicates bats as the virus’s origin.

Role of Civet Cats in Transmission

Civet cats served as the intermediate host during the 2002-2004 SARS outbreak. These animals were sold as food in markets in Guangdong Province, China, where the first cases appeared. The proximity between humans and civet cats in these markets enabled the virus’s transmission from animals to humans.

Economic and Social Impact

The emergence of SARS brought about significant economic and social disruption. First detected in 2002, its effects went beyond immediate health concerns. It had far-reaching consequences.

Healthcare System Burden

The SARS outbreak heavily burdened healthcare systems globally. Hospitals were flooded with patients, leading to shortages of medical supplies and staff burnout. This increased costs and strained resources further.

Tourism and Trade Disruption

The SARS outbreak severely hit tourism and trade, mainly in Southeast Asia. Travel restrictions and fear of infection caused a sharp decline in tourist arrivals. This led to significant economic losses for tourism-dependent industries. Global trade was also impacted as countries restricted the movement of people and goods.

Psychological Effects on Communities

The psychological impact of SARS on communities was deep. Fear, anxiety, and stigma associated with the disease caused social isolation. This disruption had long-term effects on mental health, with some experiencing PTSD and other psychological issues.

The economic and social impacts of SARS highlight the need for strong public health infrastructure. They also underscore the importance of coordinated global responses to emerging infectious diseases.

Comparing SARS to Other Coronaviruses

It’s vital to grasp the similarities and distinctions between SARS and other coronaviruses for crafting robust public health plans. Coronaviruses form a vast, varied family, impacting both humans and animals with diverse diseases.

SARS vs. MERS-CoV

SARS and MERS-CoV, both coronaviruses, have triggered major outbreaks. Their origins and how they spread differ significantly. SARS was swiftly brought under control in 2002-2004, whereas MERS-CoV has persisted, causing sporadic cases and outbreaks from 2012 onwards.

- MERS-CoV has a higher mortality rate compared to SARS.

- SARS was more contagious, leading to a larger outbreak.

- Both viruses are considered zoonotic, having originated from animal reservoirs.

SARS vs. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19)

SARS-CoV-2, the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic, exhibits similarities with SARS but also notable differences. Both are betacoronaviruses, entering host cells in a similar manner.

- SARS-CoV-2 is more contagious than SARS.

- COVID-19 has a lower mortality rate compared to SARS.

- SARS-CoV-2 has spread more widely due to global connectivity and lack of immunity.

Evolutionary Relationships

The evolutionary ties between SARS, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 are complex. All three viruses likely originated from bats, with intermediate animal hosts possibly facilitating their transmission to humans.

- Bats are considered the natural reservoir for these viruses.

- Understanding their evolutionary history aids in predicting future outbreaks.

- Research into these relationships informs the development of vaccines and therapeutic strategies.

Global Health Response and WHO Actions

The SARS epidemic underscored the necessity for a strong global health response. It prompted the WHO to take significant actions. The virus’s rapid spread across borders highlighted the critical need for coordinated public health efforts.

Initial Alert and Response Systems

The WHO’s initial alert and response systems were vital in tackling the SARS outbreak. On March 12, 2003, the WHO issued a global alert. This facilitated the quick sharing of information and coordinated international responses.

International Health Regulations Development

The SARS outbreak prompted significant revisions to the International Health Regulations (IHR) in 2005. These regulations enhanced global capacity to detect and respond to public health emergencies. They included infectious diseases like SARS.

The updated IHR required countries to improve surveillance and reporting. This ensured a more effective global response to future health crises.

The global health response to SARS and the development of international health regulations are key advancements in global health security. These efforts have significantly improved the world’s ability to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease outbreaks.

Research Advancements ince SARS

The SARS epidemic was a turning point in coronavirus research. It led to major progress in vaccine development and therapeutic innovations. This progress has greatly improved our understanding and management of coronavirus infections. It has also paved the way for future research and preparedness against outbreaks.

Vaccine Development Efforts

Significant advancements have been made in developing vaccines against coronaviruses, including SARS. Researchers have used various technologies, like mRNA-based vaccines and viral vector vaccines. These efforts have not only focused on SARS but have also contributed to vaccines against other coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19.

Clinical trials have shown the vaccines’ efficacy and safety. This offers promising results for future coronavirus vaccine development.

Therapeutic Innovations

Therapeutic innovations have also seen significant progress. Researchers have explored different treatment strategies, including antiviral medications and immunomodulatory therapies. The use of convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies has shown promise in treating severe cases of coronavirus infections.

These therapeutic advancements have improved patient outcomes and reduced mortality rates associated with coronavirus infections.

The Enduring Legacy of the SARS Virus in Modern Pandemic Preparedness

The SARS Virus has profoundly impacted global health security, reshaping pandemic preparedness. The 2002-2004 outbreak revealed weaknesses in international health systems. This led to a significant effort to strengthen surveillance, detection, and response capabilities.

The impact of SARS is seen in today’s enhanced preparedness measures. The World Health Organization (WHO) has been instrumental in this evolution. They implemented International Health Regulations, requiring countries to enhance disease surveillance and response.

The SARS experience has also driven innovation in vaccine and therapeutic development. This has been a significant advancement in virology. As we face new infectious diseases, the lessons from SARS are more relevant than ever. They highlight the need for ongoing vigilance and cooperation against pandemic threats.

It is essential to integrate these lessons into ongoing pandemic preparedness efforts. This ensures that the progress made post-SARS is not undone. It also ensures the world is better prepared to handle future health crises.

FAQ

Q: What is the SARS Virus?

A: The SARS Virus, also known as SARS-CoV, is a highly contagious respiratory illness. It was first identified in 2002. This outbreak caused significant global concern.

Q: How is the SARS Virus transmitted?

A: The SARS Virus spreads mainly through respiratory droplets. It can also be transmitted by contact with contaminated surfaces. There’s a possibility of transmission through the fecal-oral route as well.

Q: What are the symptoms of SARS?

A: Symptoms of SARS include fever, headache, body aches, and respiratory issues. In severe cases, it can lead to severe pneumonia.

Q: How was the SARS outbreak contained?

A: The SARS outbreak was contained through isolation, travel restrictions, and public health measures. Personal protective equipment played a key role in controlling the spread.

Q: What is the role of animal reservoirs in SARS transmission?

A: Bats are believed to be the natural reservoir of SARS-CoV. During the 2002-2004 outbreak, civet cats acted as an intermediate host.

Q: How has the global health response to SARS impacted pandemic preparedness?

A: The global response to SARS has greatly improved pandemic preparedness. This includes the development of international health regulations and enhanced surveillance systems.

Q: What advancements have been made in SARS research?

A: Research post-SARS has led to significant advancements. These include vaccine development, therapeutic innovations, and a deeper understanding of coronavirus infections.

Q: How does SARS compare to other coronaviruses like MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2?

A: SARS is a distinct coronavirus with similarities and differences to other coronaviruses. This includes MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, in terms of genetic makeup, transmission, and clinical presentation.