Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder that causes the thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. Over time, this can affect the heart, bones, eyes, and mental health — so understanding long-term risks and management is important. Graves’ disease is a leading cause of hyperthyroidism and results when the immune system produces antibodies that stimulate the thyroid gland to increase hormone production. Typical symptoms include unintentional weight loss, a fast or irregular heartbeat, and bulging eyes; these effects often prompt testing such as TSH and free T4 measurements.

Although medical and surgical treatments can control hormone levels, untreated or recurrent Graves’ disease can produce lasting effects beyond the gland. For example, prolonged excess hormone can weaken bone density and raise cardiovascular risk, so monitoring and tailored management matter.

This article explains the long-term implications of living with Graves’ disease, summarizes treatment options, and outlines practical steps for ongoing care. If you notice new or worsening symptoms — especially a very fast pulse, sudden weight change, high fever, or vision changes — contact your clinician or an endocrinologist right away.

What are the long-term effects of Graves’ disease?

Graves’ disease can produce lasting effects across several body systems. The most important long-term issues to watch for are weakened bones (higher fracture risk), cardiovascular problems (including atrial fibrillation), eye disease (Graves’ ophthalmopathy), and mental health changes.

Persistently high thyroid hormone levels speed up bone turnover and can reduce bone mineral density. Over months to years this raises the risk of osteoporosis and fractures, particularly in older adults and postmenopausal women.

Excess thyroid hormone also affects the cardiovascular system. Chronic hyperthyroidism increases the chance of atrial fibrillation — an irregular, often fast heart rhythm — which in turn raises stroke risk. It can also contribute to heart failure in people with prolonged uncontrolled disease.

Graves’ ophthalmopathy causes inflammation and swelling of the tissues around the eyes. Symptoms can range from dry, gritty eyes and double vision to protrusion of the eyes; in severe cases, optic nerve compression and vision loss can occur.

Mental health effects are common. Anxiety, mood disorders, and cognitive difficulties may persist even after thyroid levels normalize. Addressing these symptoms with mental health support is an important part of care.

If you have a very fast or irregular heartbeat, sudden vision changes, severe bone pain after a minor fall, or signs of severe anxiety, seek urgent medical attention. These can indicate complications that need immediate evaluation.

What is Graves’ disease?

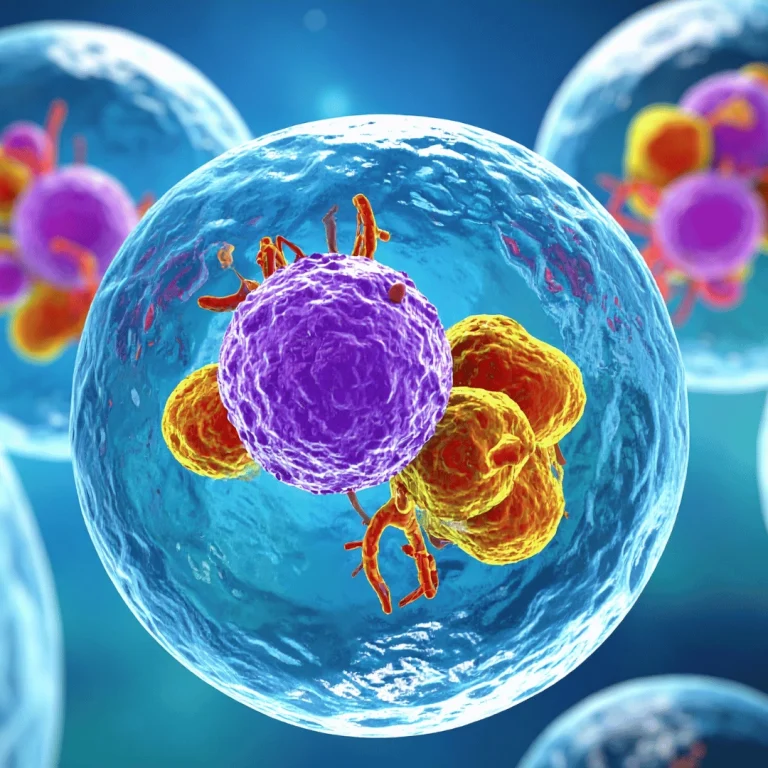

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system makes antibodies (TSH receptor antibodies) that stimulate the thyroid gland to overproduce thyroid hormones — a condition called hyperthyroidism. Common laboratory tests include TSH, free T4 and T3, and TRAb (thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin) to confirm the autoimmune cause.

The excess thyroid hormone affects many systems. Typical symptoms include:

- Weight loss despite increased appetite — the body burns more energy due to higher thyroid hormone levels.

- Nervousness, restlessness, and anxiety — common neuropsychiatric symptoms.

- Irregular or rapid heartbeat (palpitations) and tremors.

- Heat intolerance and excessive sweating.

- Diarrhea and more frequent bowel movements.

In many people, Graves’ disease causes a goiter (enlarged thyroid) and may produce noticeable eye changes (bulging or irritation) from Graves’ ophthalmopathy.

Graves’ disease is more common in women and most often appears between ages 20 and 50, though it can occur at any age. Its exact trigger is unknown; genetics, smoking, and other environmental factors may increase risk.

Learn more about Graves’ disease. If you have symptoms or suspect a thyroid problem, talk to your clinician about testing (TSH, free T4/T3 and, if indicated, TRAb) to confirm a diagnosis and start appropriate treatment.

Complications of untreated Graves’ disease

When Graves’ disease goes untreated or is poorly controlled, several serious complications can develop. Below are the key problems, a brief description of each, how common or urgent they are, and typical next steps for care.

Thyroid storm (emergency)

What it is: Thyroid storm is a rare but life-threatening surge in thyroid hormone activity that causes very high fever, extreme tachycardia, dehydration, delirium, and sometimes organ failure. The condition represents extreme thyroid gland overactivity and requires immediate hospitalization.

Urgency and triggers: It can be triggered by infection, surgery, trauma, or stopping antithyroid medication. Because it can be fatal without prompt treatment, call emergency services if someone with Graves’ disease develops very high fever, a very rapid or irregular pulse, severe confusion, or breathing problems.

Typical care: Treatment in an intensive setting includes rapid lowering of thyroid hormone effects (beta-blockers), inhibition of hormone production (anti-thyroid drugs like methimazole or propylthiouracil), supportive measures (IV fluids, cooling), and addressing the trigger (antibiotics for infection).

Heart issues (arrhythmia, heart failure, stroke risk)

What to watch for: Chronic hyperthyroidism increases sympathetic activity and cardiac workload. The most common cardiac complication is atrial fibrillation, which may present as palpitations, breathlessness, or lightheadedness.

Risks: Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of stroke because it can form blood clots in the heart. Long-standing untreated hyperthyroidism can also lead to cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure, especially in older patients or those with preexisting heart disease.

Next steps: If you have new palpitations, an irregular pulse, or fainting, seek medical evaluation. Management may include rate control with beta-blockers, anticoagulation if AF is confirmed and indicated, and cardiology referral for further assessment.

Pregnancy-related risks

Risks in pregnancy: Uncontrolled Graves’ disease in pregnancy can harm both the pregnant person and the fetus. Potential complications include preterm birth, low birth weight, and hypertensive disorders such as preeclampsia.

Management considerations: Pregnancy changes which anti-thyroid medications are safest and requires close monitoring of TSH and free thyroid hormones and coordination between obstetrics and endocrinology. If you are planning pregnancy or become pregnant, discuss medication adjustments and monitoring with your care team.

Bone loss and fractures

How thyroid hormone affects bone: Prolonged elevations in thyroid hormone accelerate bone turnover, impairing the body’s ability to maintain bone mineral density. Over time this can lead to osteoporosis and a higher risk of fractures — particularly in older adults and postmenopausal women.

Monitoring and prevention: Consider bone density testing (DEXA) for patients with prolonged hyperthyroidism or additional risk factors. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation, lifestyle measures (weight-bearing exercise, smoking cessation), and restoring normal thyroid hormone levels help protect bone health.

Eye disease (Graves’ ophthalmopathy)

What it is: Graves’ ophthalmopathy (thyroid eye disease) involves inflammation of the muscles and tissues around the eyes. Symptoms can include eye redness, grittiness, tearing, double vision, and protrusion (proptosis).

Severity and care: Mild cases are treated with lubricating drops, sunglasses, and lifestyle changes (quit smoking). Moderate to severe cases may need corticosteroids, orbital radiotherapy, or surgery; an ophthalmology referral is essential for progressive symptoms. In rare cases optic nerve compression can threaten vision and requires urgent care.

Mental health and other problems

Mental health: Anxiety, mood swings, insomnia, and cognitive complaints are common with prolonged hyperthyroidism. These issues may persist after thyroid hormone levels normalize and often benefit from counseling, psychiatric evaluation, or medication.

Skin and dermopathy: A small percentage of people develop Graves’ dermopathy (thickened, red skin, typically on the shins). It is uncommon but can be persistent; dermatology referral may be needed for symptomatic cases.

Data and frequency: The exact frequency of these complications varies by population and disease control. For example, atrial fibrillation and decreased bone density are more likely with longer duration and greater excess of thyroid hormone. Work with your clinician to interpret individual risk and plan monitoring.

Treating Graves’ disease

Treatment for Graves’ disease aims to control excess thyroid hormone production, relieve symptoms, and reduce the risk of long-term complications. Choice of therapy depends on individual factors such as age, pregnancy plans, severity of hyperthyroidism, the size of the thyroid, and whether Graves’ ophthalmopathy is present.

- Anti-thyroid medications (methimazole, propylthiouracil): Pros: noninvasive, often used as first-line for many patients and as a bridge before more definitive therapy; can restore normal thyroid hormone levels. Cons: may require months to years of treatment, relapse is possible after stopping drugs, and rare but serious side effects (agranulocytosis, liver injury) can occur. Notes: propylthiouracil is preferred in the first trimester of pregnancy; otherwise methimazole is commonly used. Typical monitoring: TSH and free T4 every 4–8 weeks during dose changes, then every 3–6 months when stable.

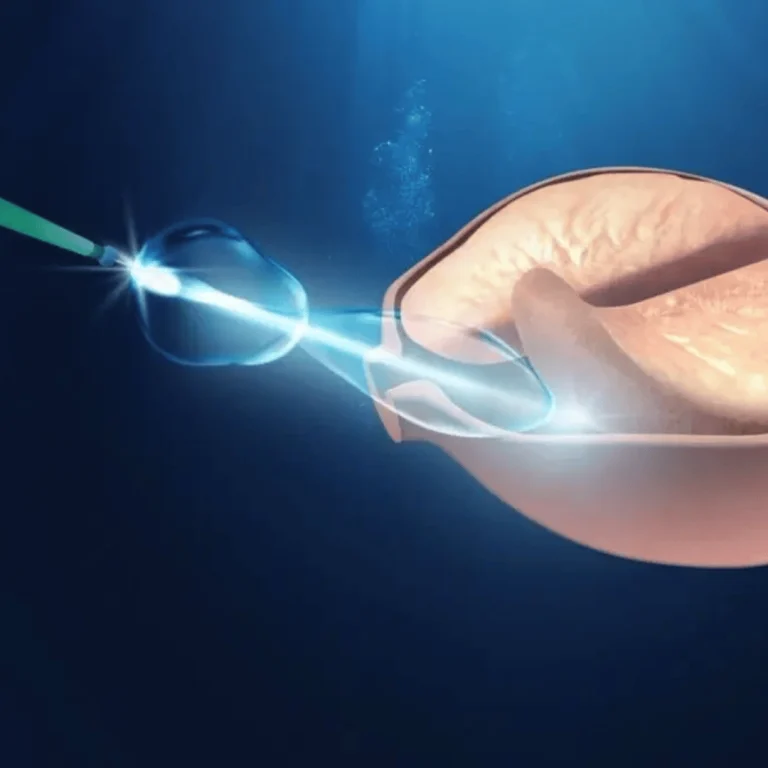

- Radioactive iodine therapy (RAI): Pros: often definitive—radioactive iodine is taken orally, taken up by the thyroid and destroys overactive cells, lowering hormone production. Cons: frequently results in permanent hypothyroidism, requiring lifelong levothyroxine; not usually recommended during pregnancy or active severe thyroid eye disease. Monitoring: TSH and free T4 measured at intervals (often 6–8 weeks post-RAI, then periodically) to detect hypothyroidism or residual hyperthyroidism.

- Thyroid surgery (thyroidectomy): Pros: immediate removal of thyroid tissue can rapidly control hormone excess and is useful for large goiters, suspicion of cancer, or when rapid control is needed. Cons: surgical risks (bleeding, infection), and like RAI, surgery commonly causes hypothyroidism requiring lifelong replacement. Consideration: surgery is often chosen when RAI or antithyroid drugs are contraindicated or unacceptable.

- Beta-blockers and symptomatic therapy: Beta-blockers (for example, propranolol) do not change thyroid hormone levels but reduce symptoms such as rapid heart rate, tremor, and anxiety while definitive therapy is arranged. Eye treatments (lubricating drops, corticosteroids, or surgery) address Graves’ ophthalmopathy directly.

Decision flow — when each option is preferred: antithyroid drugs are often used first-line or for people who want to avoid permanent hypothyroidism; RAI is common for definitive therapy in adults who are not pregnant; surgery is preferred for large goiters, suspected malignancy, or when RAI and drugs are contraindicated. For active, severe thyroid eye disease, discuss options with an ophthalmologist before choosing RAI, as RAI can worsen eye disease in some patients.

Monitoring and timelines: Expect frequent tests (TSH, free T4/T3) every 4–8 weeks while adjusting therapy, then every 3–12 months once stable. Antithyroid medication courses commonly last 12–18 months or longer, with decision for continued therapy or definitive treatment guided by response and TRAb levels. After RAI or surgery, check TSH periodically to detect hypothyroidism and start levothyroxine as needed.

Talk with an endocrinologist to weigh pros and cons for your situation. Factors such as age, desire for pregnancy, severity of symptoms, TRAb levels, and presence of ophthalmopathy determine the best pathway. If you experience new or worsening symptoms — for example, very rapid heartbeat, chest pain, severe eye changes, or fever — seek prompt medical care.

Managing Graves’ disease

Effective long-term management of Graves’ disease reduces complications and improves quality of life. Below are practical, actionable steps patients and clinicians commonly use to monitor and maintain stability.

- Regular monitoring: Expect frequent thyroid function tests when starting or changing therapy: typically TSH and free T4 every 4–8 weeks during adjustment, then every 3–12 months once stable. After definitive therapy (radioactive iodine or surgery), check TSH at ~6–8 weeks and periodically thereafter to detect hypothyroidism early.

- Heart and blood monitoring: Because excess thyroid hormones affect the cardiovascular system, monitor for palpitations and arrhythmia (new-onset palpitations should prompt medical review). People with atrial fibrillation may need anticoagulation and cardiology follow-up.

- Protect bone health: For patients with prolonged hyperthyroidism, consider bone density testing (DEXA), especially in older adults and women. Recommend weight-bearing exercise, smoking cessation, and adequate calcium and vitamin D intake to help counteract bone loss.

- Eye care: If you have eye symptoms, arrange regular ophthalmology reviews. Mild eye disease needs lubricating drops and smoking cessation; moderate-to-severe thyroid eye disease may require corticosteroids, radiotherapy, or surgery in coordination with an eye specialist.

- Mental health support: Monitor mood, anxiety, sleep, and cognition. Counseling, psychiatric assessment, or short-term medications can help manage persistent symptoms even after hormone levels normalize.

- Pregnancy planning and care: People who are planning pregnancy or who become pregnant should work closely with their clinician. Medication choices and dosing change in pregnancy — for example, propylthiouracil is often preferred in the first trimester — and thyroid function requires closer monitoring.

Maintenance checklist (practical): keep a schedule of TSH/free T4 tests, track symptoms (weight changes, palpitations, vision changes), maintain bone-healthy habits, and get annual eye checks if you have ophthalmopathy. Share test results with your endocrinologist to adjust therapy promptly.

Red flags — seek urgent care: very rapid or irregular heartbeat, chest pain, sudden vision loss or severe eye pain, high fever with confusion, or severe shortness of breath. For non-urgent concerns (worsening fatigue, mood changes, minor vision changes), contact your primary care clinician or endocrinologist for earlier review.

Work with a care team: management often involves your primary care clinician, an endocrinologist for thyroid-specific therapy and monitoring (TSH, uptake or TRAb testing when indicated), a cardiologist for heart issues, and an ophthalmologist for eye disease. Coordinated care helps minimize long-term problems and tailors therapy to your life goals, including pregnancy planning.

Summary

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder of the thyroid that can cause long-term problems in the heart, bones, eyes, and mental health when thyroid hormone levels are uncontrolled. Early diagnosis and tailored treatment reduce these risks.

Management commonly combines antithyroid medication, possible definitive therapy (radioactive iodine therapy or surgery), and supportive measures such as beta-blockers and eye care. After definitive treatment, many patients develop hypothyroidism, which is managed with lifelong replacement.

Takeaway: if you have symptoms or a diagnosis of Graves’ disease, work with an endocrinologist to monitor TSH and thyroid hormone levels, plan appropriate therapy, and schedule regular check-ups. Seek immediate care for severe symptoms such as a very rapid heartbeat, high fever, or sudden vision changes.

For reliable information and support, consider resources such as Thyroid.org and the NIH/NLM PubMed Central pages linked in this article, and discuss personal risks (especially for women of childbearing age) and timing of therapy with your care team.